By: Equal Justice Initiative

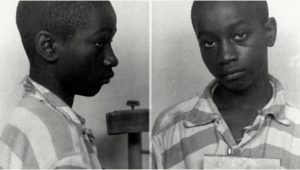

On June 16, 1944, George Stinney Jr., a ninety-pound, black, fourteen-year-old boy, was executed in the electric chair in Columbia, South Carolina. Three months earlier, on March 24, George and his sister were playing in their yard when two young white girls briefly approached and asked where they could find flowers. Hours later, the girls failed to return home and a search party was organized to find them. George joined the search party and casually mentioned to a bystander that he had seen the girls earlier. The following morning, their dead bodies were found in a shallow ditch.

George was immediately arrested for the murders and subjected to hours of interrogation without his parents or an attorney. The sheriff later claimed that George confessed to the murders, though no written or signed statement was presented. George’s father was fired from his job and his family forced to flee amidst threats on their lives. On March 26, a mob attempted to lynch George but he had already been moved to an out-of-town jail.

On April 24, George Stinney faced a sham trial virtually alone. No African Americans were allowed inside the courthouse and his court-appointed attorney, a tax lawyer with political aspirations, failed to call a single witness. The prosecution presented the sheriff’s testimony regarding George’s alleged confession as the only evidence of his guilt. An all-white jury deliberated for ten minutes before convicting George Stinney of rape and murder, and the judge promptly sentenced the fourteen-year-old to death. Despite appeals from black advocacy groups, Governor Olin Johnston refused to intervene. George Stinney remains the youngest person executed in the United States in the twentieth century.

Seventy years later, a South Carolina judge held a two-day hearing, which included testimony from three of George’s surviving siblings, members of the search party, and several experts. The state argued at the hearing that — despite all the unfairness in this case — George’s conviction should stand. The trial court disagreed and vacated the conviction, finding that George Stinney was fundamentally deprived of due process throughout the proceedings against him, that the alleged confession “simply cannot be said to be known and voluntary,” that the court-appointed attorney “did little to nothing” to defend George, and that his representation was “the essence of being ineffective.” The judge concluded: “I can think of no greater injustice.”

https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/jun/16

Africa Just another WordPress site

Africa Just another WordPress site